Tuesday, 23 May 2017

Agriculture in Africa: Potential versus reality

With more than 60% of its 1.166 billion people living in rural areas, Africa’s economy is inherently dependent on agriculture. More than 32% of the continent’s gross domestic product comes from the sector.

However, agricultural productivity still remains far from developed world standards. Over 90% of agriculture depends on rainfall, with no artificial irrigation aid. The techniques used to cultivate the soil are still far behind from what has been adopted in Asia and Americas, lacking not only irrigation, but also fertilisers, pesticides and access to high-yield seeds. Agriculture in Africa also experiences basic infrastructural problems such as access to markets and financing.

Singapore is proving to be an engaged ally in the process of changing this reality. Some big players in the agricultural sector with their headquarters in Singapore, are investing heavily in Africa. Technology and skills are being transferred to smallholder farmers and the large-scale producers are cooperating, playing a fair game that will help develop the sector and make it more sustainable.

Agriculture in Africa: An overview

In Africa, agriculture accounts for two thirds of livelihoods and food accounts for two thirds of the household budgets of poor people. It makes up a very important part of the lives of African people, but in spite of it, it apparently receives very little attention from the governments.

The low productivity levels of agriculture in Africa have resulted in a worrisome scenario: it does not meet the growing demand for food from urban centres. The region is increasingly dependent on food imports. For a continent with such a vast area, a booming young population and tropical climate, it is surprising that Africa is not a net exporter of agricultural products. In the 1970s, Africa provided 8% of the world’s total agricultural exports. Today this number has dropped to a negligible 2%.

Africa spent US$35bn on food imports (excluding fish) in 2011, only 5% of it related to trading within the continent. An increase in productivity, matched with the right set of policies and investment, could revert this situation. Africa could replace these imports with their own produce, which would in turn reduce poverty, enhance food and nutrition security, and provide sustainable growth to the respective societies.

A broader economic transformation is necessary to shift the current paradigm facing agriculture in Africa. In most of the cases, urbanization and economic growth have resulted in new opportunities for local agricultural producers. However, in Africa, this share of the market mainly belongs to foreign companies. Imports of food staples have been rising sharply, and domestic agriculture has so far failed to increase supply in response. Raising productivity in agriculture is vital to transformative growth, not just because it has the potential to expand markets by displacing imports, but also because agricultural growth is twice as effective in reducing poverty as growth in non-agricultural sectors.

How does agricultural development trigger economic growth?

Agricultural growth was the precursor to the industrial revolutions that spread across the temperate world, from England in the mid 18th century, to Japan in the late 19th century. At that time, a better understanding of the use of soil and techniques, such as irrigation, use of horsepower in the fields, and seed selection, improved crop yields. Consequently, livestock could be better fed during winter times, increasing the size of herds. These changes in agriculture made it possible to feed all the people attracted to the industrial centres as factory workers, triggering the industrial revolution and leading to higher economic growth.

More recently, we see examples of economic transformation linking better agricultural productivity to industrial growth in countries such as China, India, and Vietnam.

In the modern world, the cycle of economic growth resulting from agriculture development, is somewhat more complex than what was observed at the beginning of the industrial revolution. First, as income grows, demand for non-food items grows while demand for most agricultural products decreases as a percentage of total consumer spending. Consumers start spending more money on non-essential products, while spending on food flattens. This imbalance increases the price of non-food items relative to food prices, causing resources like labour and capital to move from agriculture to more remunerative uses in other sectors.

As economic development unfolds, education levels grow across populations. The formal education and complex skills acquired through schooling are largely required in the non-agricultural sectors. With increasing education levels, an economy sees its working force in the fields being replaced by machines and a better use of the soil and resources. Large-scale corporate farms replace small-scale family farms. In the long run, the value of farm production typically grows slower than does aggregate income, or GDP.

Over time, the agricultural sector gives up land to urban expansion, industrial and services sectors use (including recreational and tourism activities), and increasingly also for purposes of environmental conservation. That is, in a nutshell, the history of Singapore. The lack of land, however, resulted in an extreme version of the scenario and basically all the output of agricultural sector was replaced by imports.

In larger countries, these shifts can reach a balance, with a highly productive agricultural sector that provides food to a thriving urban area.

Agricultural growth in Africa

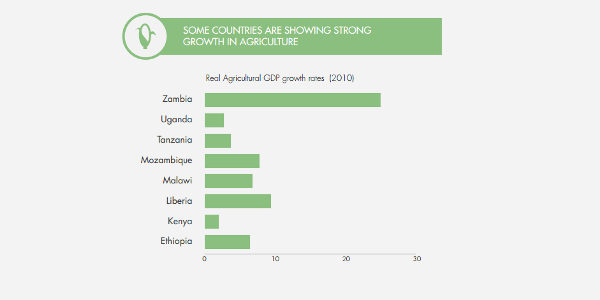

The reality of agricultural development in Africa is still far from ideal. In sub-Saharan Africa, the growth rate of agricultural GDP per capita was close to zero during the early 1970s, reaching negative figures in some years. This changed in the 1980s, when agricultural GDP growth reached 2.3% per year, increasing to 3.8% a year from 2000 to 2005. However, this increment was mainly due to an expansion in farm land, and not in agricultural productivity. African farm yields are among the lowest in the world. However, some countries have experienced a strong GDP growth in agriculture, such as Zambia, Liberia, Mozambique and Ethiopia.

Although there is a strong link between agricultural growth and decreases in poverty, the connection is not that simple. An example of this is Zambia, which experienced a vast increase in maize yields from 2006 to 2011, but did not see a reduction in poverty. Underlying inequalities and government policy explain the discrepancy. The gains in productivity in Zambia were mainly attributed to large scale fertiliser subsidies to large farms. Small farms, with areas below one hectare, received only an average of 7% of the subsidy.

On the positive side, there are two examples where agricultural growth did drive a decrease in poverty – Ethiopia and Rwanda. According to the World Bank, poverty in Ethiopia dropped by 33% since 2000, with an agricultural GDP growth of near 10% per year being the main driver.

Rwanda’s strategy was to focus its production on staple crops. While export crops typically have higher value, staple crops have a larger potential to replace imported food, which points to a promising avenue for growth that reduces poverty.

How can African countries improve their agricultural sector and use it as an engine of economic growth? The strategy will depend on each individual country, but there are a few common measures that, when put together, certainly increase the chances of a country to ignite a virtuous circle of growth fuelled by agriculture.

Increasing productivity

Agricultural productivity is related to a range of factors. The lack of irrigation is an obvious example. Only 5% of the cultivated land in Africa makes use of irrigation, with most of the farmers depending on rainfall. In comparison in Asia, 38% of the arable land is under irrigation.

Furthermore, soil health is a challenge. The average farmer in Ghana uses only 7.4kg of fertiliser per hectare, while in South Asia fertiliser use averages more than 100kg per hectare. Unsurprisingly, output per hectare in Africa falls far below the levels registered in other parts of the world. When farmers plant the same fields without using fertilisers, they literally mine the soil: an estimated eight million tonnes of nutrients are depleted annually in Africa.

The cost of fertilisers is part of the problem. Farmers in Africa face some of the world’s highest fertiliser prices, and not just in landlocked countries where transport costs are higher, like Burundi and Uganda. Farmers in Nigeria and Senegal pay three times more than their counterparts in Brazil and India. Some countries, like Ghana and Malawi, have thrown money at fertiliser subsidies in flush years only to cut back when budgets tighten. Subsidised fertiliser intended for smallholders have often been resold at market rates with middlemen pocketing the profit. Nigeria’s system became so corrupt that in 2012, the agriculture minister, Akinwumi Adesina, estimated that as little as 11% of subsidised fertiliser was actually getting to small farmers at the subsidised price.

Pesticides is another element that, if correctly used, can improve crop yield without environmental damage. This method has been increasingly adopted in the past decade across Africa in an indiscriminate fashion. The lack of education on which types and quantity of pesticide are the best for each crop, and the absence of government control, have led to its excessive use and consequent environmental contamination and human health problems.

Access to quality seeds has also a long way to go in Africa. Experts at the Integrated Seed Sector Development (ISSD) Africa seminar in Kenya pointed out that small-scale farmers in sub-Saharan Africa are unable to get full information and access to good seeds. The circulation of fake seeds is a major problem in Kenya, which hinders the transformation of the agricultural sector. Africa needs a well-functioning, market-driven seed system and research scientists working with small scale farmers to improve their seeds. The increasing degree of climate change also aggravates the situation. Aiming for improved seed varieties will help crops resist or withstand droughts and flooding, challenges that are becoming alarmingly common.

Some significant improvements have been achieved by AGRA. The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa was founded in 2006 through a partnership between the Rockefeller Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and has been helping millions of smallholder farmers in Africa. AGRA has supported more than 400 projects, including efforts to develop and deliver better seeds, increase farm yields, improve soil fertility, upgrade storage facilities, improve market information systems, strengthen farmers’ associations, expand access to credit for farmers and small suppliers, and advocate for national policies that benefit smallholder farmers. Today AGRA collaborates with more than 100 seed companies, representing about a third of the market. They produced about 125,000 tonnes of improved seed in 2015 – up from 26,000 tonnes in 2010.

In Rwanda, the One Acre Fund charity provides its clients with high yield seeds, fertiliser, know-how and credit, which in many times is the deal-break point. The increased productivity of high-yield seeds usually comes with a down point: the plants grown from them do not produce seeds of the same sort. Hence, small farmers frequently struggle to find financing to buy seeds for the next crop.

In 2015, One Acre Fund’s large network of instructors, farmers themselves, taught some 305,000 east African smallholders, developing skills such as carefully spacing seeds to maximise productivity and to apply fertiliser in an optimal way.

Lack of subsidies

Agriculture subsidies make an important factor of imbalance in the international market. Although Africa has one of the lowest cost of production of agricultural commodities in the world, it loses competitiveness in the international market as wealthier countries subsidise their famers, sometimes to the extent that the selling price of crops is lower than the production cost.

That is the reality of cotton farmers in west Africa. The United States, the world’s largest cotton producer, paid its cotton farmers $32.9bn to grow their crops between 1995 and 2012. US farmers are subsidised so they produce more cotton than they would otherwise, lowering the global price.

Members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) spent a total of $258bn subsidising agriculture in 2013. As a consequence, wealthy nations inflate their agricultural outputs to an artificial level, frequently flooding the commodities market and bringing prices down. This creates an unfair competition in the global market, where the most affected (negatively) are the small farmers in the poorest countries, where government subsidies are none-existent.

Since more than one third of the GDP of most African countries is directly related to the agricultural sector, these countries may be even more vulnerable to the effects of subsidies. They generate an indirect impact on reducing the income available to invest in rural infrastructure such as health, safe water supplies and electricity for the rural poor. Struggling to survive, many farmers migrate from rural to urban areas in search of alternative economic opportunities.

An important milestone on abolishing subsidies was achieved in the World Trade Organisation meeting held in Nairobi, in December of 2015. Developed countries have committed to remove export subsidies immediately, except for a handful of agriculture products, and developing countries will do so by 2018. Developing members will keep the flexibility to cover marketing and transport costs for agriculture exports until the end of 2023, and the poorest and food-importing countries would enjoy additional time to cut export subsidies.

The decision contains disciplines to ensure that other export policies are not used as a disguised form of subsidy. These disciplines include terms to limit the benefits of financing support to agriculture exporters, rules on state enterprises engaging in agriculture trade, and disciplines to ensure that food aid does not negatively affect domestic production. Developing countries are given longer time to implement these rules. This measures will hopefully make the global market more balanced (creating greater equity) and improve the competitiveness of smallholder farmers in Africa.

Mechanisation in agriculture

A critical step into modernising agriculture is the adoption of mechanisation in replacing human labour. Most of Africa is still far behind this stage. In sub-Saharan Africa, agricultural mechanisation has either stagnated or retrogressed in recent years. Over 60% of farm power is still provided by human muscle, mostly from women, the elderly and children. Only 25% of farm power is provided by animals, while less than 20% of mechanisation services are provided by engine power.

As observed in most parts of the world, the adoption of animal force, tools and equipment enhances the production and productivity of different crops due to timeliness, precision and improved quality of operations.

At first sight, one may conclude that the replacement of human labour in the agriculture fields by machines would result in increased unemployment. However, this displacement can be compensated by the growing demand for human labour due to multiple cropping, greater intensity of cultivation and higher yields. Furthermore, the demand for non-farm labour for manufacturing, servicing, distribution, repair and maintenance, as well as other complementary jobs, are substantially increased due to mechanisation.

Farm mechanisation greatly helps the farming community in developing overall economic growth. These conclusions were observed in a study conducted in the Punjab Agricultural University in India, but similar results were reached in other developing countries such as Bangladesh. This model will certainly bear fruits when replicated in Africa as a whole.

A study conducted by the International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research (IJAIR) in Nigeria, showed that mechanisation significantly increased the productivity of cassava fields, and that farmers who adopt mechanisation, have an increased income in comparison to those that only use human labour.

In order to be successful and sustainable, policies for agricultural mechanisation development must be tailored to local needs and must be firmly embedded in broader agricultural policy approaches. To ensure an effective transition from hard-labour jobs in the fields towards jobs related to the increased use of mechanisation, the governments have to set the right policies and incentives.

Setting the right policies

The legacy of the agricultural policy environment is evident in global and domestic markets. Africa’s farmers have a limited presence in global markets. The region as a whole exports less than Thailand. West Africa now accounts for around one fifth of world rice imports. Nigeria’s food import bill for rice currently exceeds $2bn a year. The reason: average annual rice production has stagnated at 28kg per capita since 1990, while per capita consumption has increased from 18kg to 34kg. Rice imports have been growing at 11% a year to fill the gap.

To try to counter this foreign dependence, the Nigerian government has introduced a number of key policies and investment strategies to increase domestic rice production and improve its competitiveness with imports. This is being done through a combination of import restrictions, input policy and institutional reforms, and direct investments along the rice value chain.

Its effectiveness is questionable though. Some of the measures are likely to be difficult to implement or will only have a short-term influence. This is the case of import restrictions, which may hurt consumers and farmers who grow crops other than rice. Since rice is a staple food in Nigeria, present in the daily meals of most of the population, raising its price is likely to cause inflation and affect GDP negatively.

Focusing more attention on technology change and market improvement seem more promising. A modest increase in rice yields, the expansion of high-quality varieties to replace low-quality ones, and improved processing technologies, can increase the competitiveness of domestic rice.

Singapore engagements in agricultural Africa

There are some big Singaporean-based companies engaged in ventures in the agricultural sector in Africa. Olam, for example, deals with the sourcing, processing and distribution of raw materials such as cocoa, sugar, beans, palm oil, and nuts, and is the world’s biggest supplier of cashews and sesame seeds. It began operating in Tanzania in 1994, with its head office in the capital Dar es Salaam and branches spread out in five other cities. There the company manages an integrated supply chain for four key products: cotton, sesame, cocoa, and green coffee.

In 1997, Olam expanded to Uganda, where it transacts the same products as in Tanzania, but also imports and distributes sugar and edible oil. The head office is located in the capital Kampala, and branches are spread through eight locations. Olam has a broad operation there, extending along the value chain from origination and processing, to logistics and distribution. In fact, Africa plays an important role in the company’s portfolio: 27% of total sourcing volume comes from Africa, where 29% of sales turnover is generated.

Rice extension farming in Nigeria and outgrowers’ programmes in cashew processing in Tanzania and Mozambique, exemplify Olam’s approach in linking farmers to its supply chain. In these countries, the company supports farmers through extension services, providing training, buying back produce and acquiring farm equipment.

Another example of the agricultural link between Singapore and Africa comes from Wilmar International, which in 2012 was the largest supplier of cooking oil to China and Vietnam. In 2010, the company founded a joint venture, PZ Wilmar, in Nigeria, with the aim of building a sustainable future for palm oil in that country. Palm oil is used in cooking oil, confectioneries and baked goods. Since the subsidiary was founded, it was responsible for creating up to 30,000 direct and indirect jobs; this helped reduce Nigeria’s current domestic palm oil production shortfall and import deficit.

Wilmar revitalised unproductive, previously-owned palm oil plantations and invested in new ones, helping to close the 350,000 tonne palm oil import gap. In this process, the company built a state-of-the-art palm oil refinery and packaging facility in Lagos.

Wilmar also ensures that skills are transferred via on-the-job training, to secure optimal harvests with minimal wastage. In addition, the company also owns oil palm plantations in Ghana, and through joint ventures, owns plantations in Uganda and west Africa. As at the end of 2014, Wilmar had more than 14,000 hectares of planted area in Africa.

The potential

Africa has the land, water and people needed to be an efficient agricultural producer – and to feed an expanding urban population. The Guinea Savannah, a vast area that spreads across 25 countries, has the potential to turn several African nations into global players in bulk commodity production. In addition, countries such as Ghana, Mali, Senegal, Mozambique and Tanzania, have large breadbasket areas that could feed regional populations, displace imports and generate exports.

This potential is yet far from being fully explored, but some milestones have been reached. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rwanda’s farmers produced 792,000 tonnes of grain in 2014 – more than three times as much as in 2000. Production of maize, a vital crop in east Africa, jumped sevenfold. Cereal production tripled in Ethiopia between 2000 and 2014. The value of crops grown in Cameroon, Ghana and Zambia has risen by at least 50% in the past decade.

The single most pressing challenge facing Africa’s governments is to harness the continent’s increasing wealth and use it to improve people’s lives. Agriculture is at the heart of that challenge. To reduce poverty and boost economic growth, Africa will have to develop a vibrant and prosperous agricultural sector.

Singapore is aware of Africa’s vast potential to become the world’s granary and is making the right moves to tap into this opportunity. By investing and transferring technology and skills to the local population, it ensures that best practices in agriculture can be easily adopted by future generations. The improvements achieved by Olam and Wilmar International in the continent are real examples that this is the right strategy to implement. That is how agriculture in Africa will reach the standards of productivity and quality necessary to feed their own population and also to become a net exporter of agricultural products in the near future.

African agriculture A green evolution The farms of Africa are prospering at last thanks to persistence, technology and decent government

NOT so long ago Jean Pierre Nzabahimana planted his fields on a hillside in western Rwanda by scattering seed held back from the last harvest. The seedlings grew up in clumps: Mr Nzabahimana, a lean, muscular man, uses his hands to convey a vaguely bushy shape. Harvesting them was not too difficult, since they did not produce much.

This year the field nearest to his house has been cultivated with military precision. In February he harvested a good crop of maize (corn, to Americans) from plants that grew in disciplined lines, separated by precise distances which Mr Nzabahimana can recite. He then planted climbing beans in the same field. On this and on four other fields that add up to about half a hectare (one and a quarter acres) Mr Nzabahimana now grows enough to enable him to afford meat twice a month. He owns a cow and has about 180,000 Rwandan francs ($230) in the bank. Although he remains poor by any measure, he has entered the class of poor dreamers. Perhaps he will build a shop in the village, he says. Hopefully one of his four children will become a driver or a mechanic.

Latest updates

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rwanda’s farmers produced 792,000 tonnes of grain in 2014—more than three times as much as in 2000. Production of maize, a vital crop in east Africa, jumped sevenfold. Agricultural statistics can be dicey, African ones especially so. But Rwanda’s plunging poverty rate makes these plausible, and so does the view from Gitega. Another farmer, Dative Mukandayisenga, says most of her neighbours are getting much more from their land. Perhaps only one in five persists with the old, scattershot “broadcast” sowing—and most of the holdouts are old people.

Rwanda is exceptional. But in this respect it is not all that exceptional. Cereal production tripled in Ethiopia between 2000 and 2014, although a severe drought associated with the current El Niño made for a poor harvest last year. The value of crops grown in Cameroon, Ghana and Zambia has risen by at least 50% in the past decade; Kenya has done almost as well.

Millions of African farmers like Mr Nzabahimana have become more secure and better-fed as a result of better-managed, better-fertilised crops grown from hybrid seeds. They are demonstrating that small farmers can benefit from improved techniques. Despite some big, much-publicised land sales to foreign investors, almost two-thirds of African farms are less than a hectare in their extent, so this is good news. Progress need not mean turfing millions of smallholders off the land, as some had feared—though by making them richer it may yet give them and their children the means to move, should they wish.

For the time being, though, more than half of the adult workers south of the Sahara are employed in agriculture; in Rwanda, about four-fifths are. With so many farmers and not much heavy industry, boosting agricultural productivity is among the best ways of raising living standards across the continent. And there is a long way to go. Sub-Saharan Africa’s farms remain far less productive than Latin American and Asian ones. The continent as a whole exports less farm produce than Thailand.

The revolution will not be broadcast

Since 1961 the total value of all agricultural production in Africa has risen fourfold. This is almost exactly the improvement seen in India, which sounds encouraging; after all, India had a “green revolution” during that time. But whereas Indian farmers got far higher grain yields per hectare, in Africa much of the new production just came from new land. In the early 1960s sub-Saharan Africa had 1.5m square kilometres given over to arable farming; now it uses 800,000 square kilometres more.

Another thing African farming had more of was people. Even today, when population growth has slowed in rural Asia and Latin America, in rural Africa it is still 2%. More people meant more workers, which can mean more yield from a farm in absolute terms. But it also meant more mouths to feed. Africa’s population grew more steeply than India’s, and as a result production per person fell in much of the continent during the late 20th century.

The explanations for Africa’s difficulties begin with geology. Much African bedrock is ancient, dating back to before the continent’s time at the heart of a huge land mass known as Gondwanaland. For hundreds of millions of years Africa has seen little of the tectonic activity that provides fresh rock for the wind and rain to grind into fertile soils. There is some naturally fertile land in the south and around the East African Rift, which runs through Rwanda. But much of the interior is barely worth farming (see map).

Only about 4% of arable land south of the Sahara is irrigated, so local weather patterns determine what can be grown. Those patterns vary a lot from time to time and place to place. Variations in time make farmers more inclined to stick with hardy but low-yielding varieties of crop. Variations in space mean that crops and diets differ a lot across the continent. In Rwanda, white maize and beans are the staple foods. In other places millet, teff, sorghum, cassava or sweet potatoes are more important. Asia’s green revolution was a comparatively simple matter, says Donald Larson of the World Bank, because Asia has only two crucial crops: rice and wheat. Provide high-yield varieties of both and much of the technical work is done. African agriculture is so heterogeneous that no leap forward in the farming of a single crop could transform it. The continent needs a dozen green revolutions.

Humans have added to these handicaps in all sorts of ways. Beginning in the 1960s, Africa’s newly independent nations—often, thanks to colonial borders, small and landlocked—taxed farm produce heavily to finance industrial ventures which often failed. They did little to improve the colonial era’s scant and inappropriate infrastructure, which tended to concentrate on railways from mines to ports. Africa still has a thin road network; in rural areas the roads are often primitive and impassable after a heavy shower.

Governments frequently imposed price controls, reducing what farmers could earn. And in some places, such as Ethiopia, farmers were subjected to oppressive command-and-control regimes that sapped their will to work. “We lost two and a half to three decades,” says Ousmane Badiane of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

The sorry history of fertiliser subsidies shows the cost of official ineptitude. Worldwide, about 124kg of artificial fertiliser is used per hectare of farmland per year. Many would argue that this is too high. But the 15kg per hectare in sub-Saharan Africa is definitely too low (see chart). Some countries, like Ghana and Malawi, have thrown money at fertiliser subsidies in flush years only to cut back when budgets tighten. Subsidised fertiliser intended for smallholders has often been resold at market rates with middlemen pocketing the profit. Nigeria’s system became so corrupt that in 2012 the agriculture minister, Akinwumi Adesina, estimated that as little as 11% of subsidised fertiliser was actually getting to small farmers at the subsidised price.

Like the clumps of earth that African farmers whack with their hand hoes, these natural and human obstacles are stubborn and hard to break down. But bit by bit they can be worn away. African agriculture is improving not because of any single scientific or political breakthrough, but because the things that have retarded productivity for decades, both on the farm and off, are being assailed from many sides.

For farmers, perhaps the most potent symbol of change is hybrid seed, often dyed a bright colour and usually burdened with an unlovely name, such as SC719. Joe DeVries of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, based in Kenya, says that by raising the prospect of higher yields, these seeds persuade farmers to spend money and time on fertiliser, weeding and pesticides. Today AGRA collaborates with more than 100 seed companies, representing about a third of the market. They produced about 125,000 tonnes of improved seed last year—up from 26,000 tonnes in 2010.

Many of these seeds are being developed in Africa for Africans. N’Tji Coulibaly of the Institut d’Economie Rurale in Mali has developed six hybrid maize varieties. Because these tolerate drought well, they can be planted north and east of the capital, Bamako, in fields where sorghum is now the dominant crop. As though in retaliation, another nearby team has created a variety of sorghum that yields about 40% more than the indigenous kind even without additional fertiliser.

Governments and charities are rushing to teach farmers how to plant the new seeds. In Rwanda, One Acre Fund, a charity, provides its clients seeds, fertiliser, know-how and, crucially, credit. To upgrade to hybrids means changing to a system where new seed has to be bought every year, because the plants that grow from hybrid seed do not produce seed of the same sort. And small farmers are usually starved of credit—one large survey for the World Bank found that only 1% of Nigerian farmers borrowed to buy fertiliser.

Last year One Acre Fund’s large network of instructors, farmers themselves, taught some 305,000 more east African smallholders skills such as carefully spacing seeds so as to maximise productivity and measuring fertiliser using bottle caps. Mr Nzabahimana is a client, as are about a third of the farmers thereabouts. In parts of Kenya where One Acre Fund has been operating for at least four years, even the farmers who are not clients get about 10% more maize per hectare than similar farmers in areas where the charity recently arrived. Know-how spreads.

Too few trucks, too many tariffs

Untouched, if marginal, land used to be plentiful in Africa. Today it is rare, so farmers must work out how to grow more on each plot. And even countries with plenty of land have little to spare near their growing cities; given the difficulties of moving fresh produce over long distances that makes intensification near the big markets particularly attractive. These urban markets can also change what farmers grow. Farmers close to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, are switching from red teff to fancier white teff because that is what city folk increasingly want. White teff is harder to grow, so the farmers are using more fertiliser and improved seed. Elsewhere, urban hunger for meat and eggs is persuading more farmers to keep cows and chickens.

Poor roads are not the only reason it is hard to move farm produce long distances. In 2013 the UN estimated that African businesses that exported goods to other African countries faced average tariffs of 8.7%, compared with 2.5% for those that exported goods beyond Africa. But the tariffs and barriers are gradually coming down. Maximo Torero, a division director at IFPRI, points out that 31% of the food calories exported from African countries went to other African countries in the mid-2000s—a low proportion, but an improvement on the 14% rate ten years earlier. The El Niño droughts of the last few months in Ethiopia and southern Africa have not yet led to widespread bans on food exports.

Reform has been slower in another area. African farmers often have few or no rights over the land they work. Insecure farmers tend not to invest much, either because they do not see the point or because they cannot get credit. These problems can be particularly bad for women. One study in Ghana found that women farmers were less likely to let their land lie fallow (a simple way of increasing its fertility). They seem to have feared losing it if they did not plant it continuously.

Well-intentioned attempts to entitle farmers have sometimes made things worse for women: as customary rights are replaced with legal ones, men tend to assert control. Still, things are improving in a few countries. In Ethiopia, where land is formally owned by the state, farmers’ rights to cultivate it and rent it out have been clarified. That reform, combined with a change to family law, seems to have increased women’s control. The Rwandan government has changed inheritance law to give women more rights.

Few of these benign changes would have taken place without a rash of superior government. Sub-Saharan Africa still has some awful regimes in Equatorial Guinea and Zimbabwe (where agricultural productivity is dropping). It has some failed states such as the Central African Republic, South Sudan and Somalia. Yet some terrible rulers have gone and border wars are rare.

In part as a result, the region is more placid than it was. The Centre for Systemic Peace, an American think-tank, tallies civil and ethnic conflicts, assigning them a seriousness score of one to ten. Between 1998 and 2014 the total conflict score in sub-Saharan Africa fell from 55 to 30. More peaceful land is more productive. So is land where the people are healthier. The World Health Organisation estimates that 395,000 Africans died from malaria in 2015, compared with 764,000 in 2000. New HIV infections are down by about two-fifths in the same period.

There is still much to do. When Mr Nzabahimana wants to sell food, he simply hawks it around the village or hires a woman to carry it on her head to Rubengera, a tiny market town a few miles away. He does not know in advance what price his crops will fetch. As Africa’s fields grow more productive, such thin, fragmented markets are becoming a bigger problem. Too few agricultural buyers reach villages, and the ones that make it can often dictate prices. “The traders have all the information—they pay the farmers what they want,” says Mr Adesina, who is now head of the African Development Bank.

Technology can help, to an extent: in Kenya, where mobile phones are ubiquitous, farmers can subscribe to services that give them price data. But rural roads will have to improve, as well as rural phones, if smallholders are to obtain better prices. So will the ability to store crops somewhere other than in their houses, where the weevils get them. Processing foods near farms, something Mr Adesina is keen on, would help reduce such waste and provide decent paying jobs.

A lack of clouds on the horizon

Another boost would come from better livestock. Far more of Africa is grazed than is planted, and demand for animal products is rising. Yet there are few meaty analogues to hybrid seeds. African cows are increasingly crossbred with European breeds to create tough animals that produce lots of milk; fodder yields are improving, just like yields of other crops. But animal vaccines remain expensive and are often unavailable, since they need to be kept cold. A pastoral revolution remains in the future.

Mr Adesina likes to say that African agriculture is not a way of life or a development activity; it is a business, and it is as a business that it will grow, through investment and access to markets. That said, it will remain a risky business, one in which a vital input, rain, cannot be controlled—as millions of farmers are regretting at the moment.

One way to face that risk is to encourage irrigation, especially water-hoarding drip-irrigation. Another is to offer some sort of crop insurance that pays out in particularly bad seasons, as Ethiopia is trying to do. Both are good options. How much they can do in the face of increasing climate change, which is likely to render the dry parts of the continent drier still, and which will do some of its damage just by making peak temperatures even hotter, remains to be seen. Some crops may become impossible to grow in the places where they are grown today.

As with hoes and hard soils, there are no easy breakthroughs to be had. But for a long time Mr Adesina’s idea of African agriculture as a business to build up would have seemed alien inside the continent and fantastical beyond it. That it no longer does is as strong a basis for hope as any.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)